HARPUR PALATE

macaulay glynn interviews nick flynn // nov/dec 2020

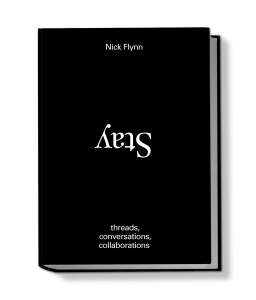

Some of Nick Flynn’s latest books include his 2019 poetry collection I Will Destroy You (Graywolf Press) and memoir This is the Night our House will Catch Fire (W.W. Norton, 2020). His most recent multimodal, multidisciplinary collection Stay (ZE Books) recalls decades of Flynn’s encounters, travels, and histories. Organized into a series of threads, this text introduces projects, friends, conversations, and frames all things as collaboration: collaborative thought, collaborative learning, collaborative finding-your-way. In a long thread titled “Notes on Racism (Mine),” bearing witness is, at once, an impossibly individual and collaborative act. I had the opportunity to converse with Nick over email following his virtual visit to Professor Tina Chang’s poetry seminar at Binghamton University. Here is the conversation we had:

MG: Your most recent volume, Stay, was an interactive text, for me. The index of notes in this book had me reading articles (notably Adrienne Rich’s “The hermit’s scream”), searching for films, watching YouTube videos, or visiting the Drone Alert Sutras online. Had I not followed these paths, I would have missed out on an entire dimension of this book. Is this kind of interactive element something you wanted the text to achieve?

NF: I love that’s what the book led you to…that’s how I relate to the world as well, one thing leads to another…whatever other experience anyone has with the book, though, is fine by me. I can imagine someone taking it into the wilderness and using it as a series of scores for performances that only the trees will witness…that would also please me.

MG: A poet’s role as a researcher, IMO, isn’t discussed enough. Can you describe your relationship to research, or ways it has evolved within your practice as an artist?

NF: I suggest to my writers that they hold off on research for as long as possible, especially if writing about something deeply lyric, memory-based…it seems important to get down on paper what your particular memory of an event is, before you try to track down the facts of that event. Once you get the official version, your interior version will begin to fade, which is a shame. Of course, if you’re writing a piece that is purely non-fiction, or even fiction based on actual events, you will likely need to go to research sooner. I would still resist, for a while at least.

MG: I will also say it has been difficult to form questions about Stay without interrupting myself and realizing that on some other page, within a different thread, an answer to a question I’ve posed can be answered, or the question is otherwise already accounted for. This is thrilling and maddening at the same time but makes the book an object that can be read again in different directions, sort of like an ontological Choose Your Own Adventure novel.

NF: Putting it together was a similar experience, in that I went over thirty years of collaborations and writing and interviews, and began seeing patterns, until I was in the midst of what Audre Lorde refers to as “meteor showers all the time, bombardment, constant connections.” A few resonant images have appeared in all my work—fire, donuts, the Atlantic, boats, alcohol, etc—they may read like obsessions, but I believe they are more deeply embedded in the subconscious (though one might rightly say that all obsessions are embedded in the subconscious).

MG: Stay is organized by seven sections or “threads.” I wondered if this was a reference to your mother’s maiden name, Draper, signifying a lineage of wool merchants. Am I reaching here? I was struck by how this initial framing destabilizes distinctions between “personal” or familial history and the material history of the world, i.e. the industrial revolution, world wars, global capitalism.

In what ways are you critical of the short-term view of one’s personal history that memoir, as a genre, typically foregrounds?

NF: I love that the threads mirror the family business (wool), for you. For me that was yet another unconscious connection. The titles of each section, yes, attempts to frame the particular (my mother, my father, etc) with the historic / archetypal / universal (Sleeping Beauty, Nebuchadnezzar). Everything we wrestle with, which in the moment is utterly personal and intimate, is also connected to everything that has come before. My mother read fairy tales, and then in some way she acted out those fairy tales, became a character in them.

MG: Your workshops have a reputation for being hands-on, tactile; in a recent virtual class visit to Binghamton University, you described asking workshop participants to bring in a xeroxed copy of a science article and twenty unfinished poems from which one can breathe new life into a few chosen lines. I remember reading Another Bullshit Night in Suck City in a workshop—we talked about how you were said to have spread all the pages out to decide the order, creating the narrative from individual pieces.

NF: It’s why I work with so many other artists—first, because I like them, and also to get a sense of the way they approach their work. The method I talked about at BU is one that is much like an artist’s workshop, where we spend some time approaching language as a material substance, able to be moved around until it looks, or feels, right. To keep it as fluid as possible, for as long as possible. It seems unrealistic to simply sit at a computer and expect a book to emerge, at least one as fully alive, embodied, as you are.

MG: Stay seems to be an extreme form of that practice: arranging decades of collaboration and thousands of words that both stand alone and that add up to something else. How long did it take to compile this volume? How did you decide what to include, what to leave out? What parts of this process were most challenging?

NF: I had been imagining Stay for many years, as an archive of all the collaborations I’ve done, and the writing that has come out of those collaborations. To do it, though, I had to study the concept of the archive, not as a dead system, but as a living one. I taught a workshop for a couple semesters where the concept of the archive was the focus, mainly around how artists (Miriam Ghani, Pad.ma, Martha Rossler, Zoe Leonard, etc) have approached it in the last couple decades. I think that helped prepare me for Stay. It is hard to say how long it took, as I’d been working on it for thirty years, in some ways, and in other ways it fell together quickly.

MG: The field poet is a central figure to Stay, especially in the thread “Notes on Racism (Mine).” One of the features of this work that I find so compelling (but struggle to describe) is the way that the narrator leads the reader along to a certain point and slips away as the reader is introduced to what the field poet has witnessed. Can you talk about your relationship to that figure?

NF: The concept of the field poet is from Vietnam, where a poet was assigned to every battle unit, and that poet’s job was to write a poem each day to commemorate what had happened. Vietnam is a highly literate culture—there is a thousand-year-old temple of literature in the center of Hanoi. The field poet was not separate from the other soldiers, which is perhaps why at some point, as a reader, you feel him slip away. You become the field poet.

MG: One of your collaborations included a project to create a “New Dictionary of Hope” following the [actually] stolen election in 2000, to which you contributed “Jubilee.” In light of this year’s presidential election, what word might you redefine?

NF: Wait, this is more of an assignment than a question. I contributed a few more words as well to the Future Dictionary of America: “homeless” as an archaic term, a couple others. They gave me a few weeks to come up with my entries. Hope takes time. Ask me again in a month. Or at least after this current regime of cruelty and greed and stupidity shuffles offstage.

MG: Can you provide a glimpse of your writing routines, if you follow any?

NF: It depends on what project, if any, I’m in the middle of at that moment. Let me tell you what I am doing today: I made a series of collages, and now, each morning, I take one with me (I choose it randomly, and don’t look at it until I’m ready to write) and write a poem simply describing it. Also, I meditate before I write anything. That said, I’ve been enjoying the time when I am not in the midst of a project, which after so many years of always being in a project feels a little like getting released from prison.

MG: Do you listen to music as you write? References to David Bowie, Iggy Pop, Springsteen… appear in your work. Are there albums you associate with the books you’ve written?

NF: Yep, each book has a soundtrack. For the last couple I’ve made playlists on Spotify, which I listen to daily to get back into that space. Mostly I listen to ambient, trancy stuff, stuff without lyrics, as the clash of language can be distracting. But in the revision process I open it up to whatever.

MG: Can you talk about some of the texts that have influenced you in terms of the way they break ‘rules’?

NF: So many….I did a virtual public slow-read / discussion of Moby Dick this past summer, a book that always amazes me with the range of tones and diction and genres it plays with. It is a book that gives us all permission. In this way it is an urtext for all the hybrid stuff to follow.

MG: What is the most exciting book or essay you’ve read recently?

NF: I just had a virtual discussion with Ross Gay last week, after he performed his epic, book-length poem Be Holding. It is one sentence, with many tangents, of course, but centered around watching (on YouTube) a mythic basketball play from 1980—Dr. J—it was thrilling. Also a shout out to Tommy Orange’s There, There, especially that first chapter. And have you read Madeleine is Sleeping, by Sarah Shun-Lien Bynum….? She’s another one that breaks all the rules. Oh, and Brenda Hillman is a goddess—her recent poem “Winter Song for One Who Suffers” blows me away. Go find it now.

Nick Flynn has worked as a ship’s captain, an electrician, and a caseworker for homeless adults. Some of the venues his poems, essays, and nonfiction have appeared in include the New Yorker, the Nation, the Paris Review, the New York Times Book Review, and NPR’s This American Life. His writing has won awards from the Guggenheim Foundation, the Library of Congress, PEN, and the Fine Arts Work Center, among other organizations. His film credits include artistic collaborator and “field poet” on Darwin’s Nightmare (nominated for an Academy Award for best feature documentary in 2006), as well as executive producer and artistic collaborator on Being Flynn, the film version of his memoir Another Bullshit Night in Suck City. His most recent collection of poetry, I Will Destroy You, appeared from Graywolf Press in 2019. He is part of the creative writing faculty at the University of Houston, where each spring he teaches workshops in poetry, creative nonfiction, and interdisciplinary art. He lives in Brooklyn with his wife, Lili Taylor, and his daughter, Maeve. His work has been translated into fifteen languages. www.nickflynn.org

Macaulay Glynn is the recipient of a Marion Clayton Link Endowment creative writing fellowship, and a 2020 winner of Epiphany literary journal’s Breakout 8 Prize for poetry. She has served as director of the Binghamton Poetry Project, which provides free writing workshop programming to the community in cooperation with the Binghamton Center for Writers, donors, and local venues. She is a poetry editor at Harpur Palate and an assistant reading series curator for New York Quarterly.