“If you can’t laugh at yourself, I don’t think you’re ready to write a memoir”

“If you can’t laugh at yourself, I don’t think you’re ready to write a memoir”

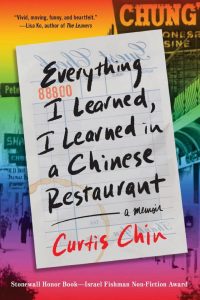

—an interview with Curtis Chin

by Derek Ellis

Derek: Hi Curtis, First, I just want to thank you for agreeing to this interview. It’s an honor to be here with you today and to have had the privilege of reading your book. Restaurants are rife with characters, life lessons, and experiences. There are two primary locales in the book, Chung’s and then later Drake’s. I was wondering how working in restaurants shaped the way you move through the world?

Curtis: Well, the simplest answer is that it teaches you customer service. I was one of those kids that wasn’t in the kitchen, but in the front of the house. So, from a very early age I had to interact with people. So, you have to learn how to listen to people and figure out what they want. So, whether it was at Chung’s or Drake’s, I had to learn how to do that.

Derek: The clientele for both of these places, were they similar or different? And if so, how?

Curtis: Well, the clientele at Chung’s, being in the inner city, was diverse. Literally, everybody from the mayor on down to the pimps and prostitutes.that diversity was much more evident along class lines. But I would also say, along racial lines, probably a lot more people of color.

When I went off to college in Ann Arbor, it was a much more white city. So, the clientele was overwhelmingly white and college educated because we were right on campus.different, but the people who went to Drake’s were more the artsy fartsy bohemian types.they had a certain edge to them in some ways. Those types of people were also at Chung’s, but Chung’s had a much more variety.

Derek: Yeah, Chung’s seemed to have a bit of everything!

Curtis: Yeah! It did. That’s one of the great things about Chinese restaurants, and everyone seems to go there, at least to me. It’s an easy place to go!

Derek: And the food is delicious, you go in for the Orange Chicken but then you’re captivated and you go in for more and more…

Curtis: Yeah, you start there and start to become more and more adventurous. I think it’s said that Chinese Food is, after pizza, the most eaten food in America. If you actually look at google searches, Chinese restaurants are number one and it’s not even close. I think the next one is Mexican food, but it’s not even close! Chinese food is almost double!

Derek: Right, always a local shop with a loyal following and that sort of thing. Now, is this some of the research aimed at your current project of a docuseries on Chinese restaurants in America?

Curtis: Yeah, my day job is working in TV and film,it seemed like this would be a good segway for me after writing this book to do a project on it. Also because I’ve been traveling around giving book talks, people whose families ran Chinese restaurants would approach me and give me some of their history, and it was interesting to start mapping that all out. It was fascinating because you can then extrapolate larger ideas and understandings of America through that, especially through that immigration pattern in particular.

Like, the type of Chinese foods available was initially a lot of chop suey joints that were from the southern Chinese, which is where my family is from. Then you move into the 50s when you had a lot of people coming in from Taiwan, but they were actually originally from Hunan and Sichuan—they were escaping China. So, they were bringing that food. Then, when America normalized relationships with China, there was suddenly Shanghainese and Mandarin food. You can see the evolution of, not just of the immigrant Chinese population in America, but in some places geopolitics between what was going on between the U.S. and China.

Derek: And I love, too, that you are exploring all of this through the lens of food. Something easily accessible, something we all have experiences with, but also for people who don’t actively think about these things. You can utilize this to shine a light on and showcase a broad swath of historical information.

Curtis: Exactly! For instance, one of the recent trends is this idea of large chains from China and Asia coming to America. Whether it’s places like Din Tai Fung (there’s a lot of them in California), or even Boba Shops, and Jollibee. What does that say about the notion of soft power? Because historically America has always exported our fast-food restaurants, and it has gained us a lot of influence through places like McDonalds or KFC. What does it mean now that Chinese restaurants are coming here? What does it say about the dominance of Asian culture now that they can reverse that trend? It’s fascinating to me!

Derek: Yeah, and that leads me to my next question, speaking about the history of food and how it enacts a power dynamic shift. You’ve spoken elsewhere about your idea that Chinese food is a large part of the fabric of American society. Which I totally agree with! But one of my favorite authors, and food enthusiasts, Anthony Bourdain, once said that he felt that the dinner table was the great leveler—that everyone would gather around and it was a central meeting place. But when he was in Beirut in 2006 when war broke out, he famously recanted his statement saying he wasn’t sure anymore. I think he was speaking towards the idea that food, the dinner table, was a place where people could meet and share the human experience. Though, now, I think that also seems a bit cynical.

But I bring it up because you were growing up in Detroit during the 80s, where the murder of Vincent Chin took place, but also you say in the memoir that by the time you were a teenager you knew 5 people who were murdered. But with Chung’s being in the red-light district of Detroit, you were in an area that was, for lack of a better term, violent. So, growing up in Detroit during such a tumultuous time, and working at Chung’s, how did you navigate the relationship between food and it being a force for change (if that is a thing?).

Curtis:

No, yeah. Well, I didn’t think of it that way as a kid, you know? I just thought it was so great that the whole city seemed to come to our restaurant. Even though we were there as much as 80 hours a week working, I felt like I got to know the city because people were coming in and sharing their stories. I don’t know how that speaks to your question, but when you were speaking about Anthony Bourdain, the thought that jumped to my head was about the election that just happened this past Tuesday.

Now, suddenly we hear people saying they’re not going to have thanksgiving with their family after finding out about who they voted for. And I think that kind of rot, or that kind of division, in American society has gotten deep—it’s quite sad. But I also don’t blame people because I’ve felt that way too, but I try to fight that urge. I’m not a knee jerk, anti-the other side kind of person. And I would like to think that food is one of the things that can bring us together. Because one of the things in American society is that we don’t have local gathering places anymore…and it’s only gotten worse since COVID. We are sort of isolated in these little silos, and if there’s anything that’s going to literally bring people back to the table it will be food. Now, whether or not food is able to do that or not is a different question.

Derek: It’s Interesting, too, that you bring up COVID as a moment where things like that began to disappear. For me, I was managing a local brewery and restaurant in the D.C. area at the time. But when COVID settled in, the restaurant closed its door and I, like many other food workers, lost our jobs with the closing of those communal spaces. It was then I had to return to Kentucky and, well, have that thanksgiving dinner with my family that I had been putting off at the time.

Curtis: Oh, you didn’t want to have dinner with your family due to the election? Or COVID?

Derek: No, no. I think it took some time for me to come to the realization that change can’t happen in that kind of stalemate. That you have to interact with them. And if you can’t change them you sort of reach for something to put into your mouth, like, “Ah, yes, lovely…roll!”

Curtis: Ha, yeah! I think you have to interact with them! But I think that is my biggest concern with the country right now—the division. I don’t like it, and I hope that we can take steps to come together.

I liken it to my book in the sense that I wrote a book about a gay Asian kid growing up in Detroit. My sense is that there’s a third of the country that are like, “Wow, that’s great! Gay Asian memoir—I’ll read that!” and then there’s a third that’s like “Gay Asian memoir, ban that book right now!” and then there’s a middle third of the country that might be curious and want to learn more. I think that’s where our country has always been, a fight for that middle third. You know, at this point, the thing that pivots all these discussions is difference and diversity.

Derek: No, no, I agree with you. I think, also, with you and I coming from a working-class background has a lot to do with seeing the frustrations felt by a good deal of the American people, but also understanding how to navigate that. Perhaps to try and reach towards that middle third, as you said.

Curtis: Right, you know, working in restaurants we, again, learned how to listen and try to understand what it is people want. Hopefully, of course, what they want isn’t a part of some fringe agenda.

The thing to understand is that there are people who are frustrated. People who are living paycheck to paycheck. People who don’t spend time, or have time, to understand what is going on in the country and how it operates. So, they are looking for someone to blame because it simplifies something that is rather large, right? But again, I mean, the income gap in this country has kept expanding for years and years and years. Don’t we find it obscene that there’s an individual on this planet that has 200 or 300 billion dollars? Do we not, as a society, find that utterly disturbing? To me, I’m a capitalist. I believe in people working hard and there being a reward, but there has to be morals to where you understand that you don’t need 10 homes when people are homeless—that you don’t need multiple yachts when there are people suffering.

Derek: And I think this harkens back to your idea that we don’t have communal spaces anymore where ideas can be shared. Then COVID isolated us even further. Now, many of the ideas people hold are regulated through the media they take in. Do you think if we had those spaces, where more stories and ideas could be openly exchanged, would help us reach that middle third that you spoke about and actually usher in change?

Curtis: Oh, absolutely! Well, as long as people are willing to have those conversations. You could be in the space with other people, but if you aren’t willing to listen then nothing will change. But I do think this has been a long conservative effort that has been decades in the making, right? How do you control a populace? You keep them ill informed.

Derek: No, no. I think you’re right in that there’s a push to control the information that people are given. With the lack of these spaces for people to interact with people who differ from them, it becomes easy to isolate people, and remove avenues for critical thinking and empathy.

It reminds me of a moment in the book where there’s a young woman who comes into Drake’s who is mean to you at first, calling you a “Banana—yellow on the outside, but white on the inside” but then invites you to the Asian American club meetings, which, when you start attending, leads to you becoming involved in learning more about Asian American history and promoting it. Do you think being an active member in a public space, like the ones we are talking about, also helped you begin to consider your role in public policy?

Curtis: Hm, yeah. I think that in public spaces listening encourages curiosity; hearing different opinions. In that sense, it shapes my sensibilities about policies. I do try to stay empathetic to the other side, and it is hard because on one hand I am thinking “Do you not see the danger of this? Does it not matter to you?” But then part of me is saying, “Well, this is what it means to live in a Democracy.” Right? Democracy doesn’t require that everybody agrees on the best choice. Democracy only requires that everybody gets to make a choice. All I can do is play the long game and ask, “How can I contribute to the public discourse that’s happening and could eventually impact them so the people don’t continue voting the way that they do.” That’s the only role that I can play…

Derek: So, shifting gears, Your book is about much, but first and foremost about growing up in Detroit. You shift to Ann Arbor later in the book. You still go back to Detroit, but it’s later about the feeling of leaving that place that you owe much to. For instance, I left Kentucky years ago, but had to come back due to COVID. And when I came back, I came back with a new vision. I was a new person, and it influenced how I saw and interacted with my family, the people who lived there who probably didn’t think the way I thought anymore because I was no longer the boy who left wearing his rebel pride hat.

Curtis: So, when you left, you felt like you were in lock-step with them and were you surprised by those changes?

Derek: I think I was surprised to feel that way. To come back and feel a sense of empathy… I left because I wanted to get out, I wanted a bigger world. I started to realize that I was living in a bubble out in the middle of the woods.

Curtis: Were you open to the idea that you might come back a changed person? Or the hope that you might come back as a changed person?

Derek: I think, subconsciously, I thought about the act of leaving…and maybe had a hope. But ultimately, I think I just wanted to get away, to get out. But that’s why I bring it up. Because in the book, I felt a kinship with your desire to leave and get out…

Curtis: Ha, yes! I understand. You know, for me, leaving it was the idea of safety. Not physical safety, which is the ironic thing. Because, you know, growing up in Detroit, I never felt unsafe. I don’t know why. Maybe it was because everybody loved our restaurant and there’s this idea about crimes in that they don’t often hit the places that they like, you know what I mean? So, I always felt safe there, physically. It was only after I left Ann Arbor that I felt unsafe for my parents. And then, why I had to leave Michigan, was because I decided I wanted to be a writer and I didn’t feel safe—I didn’t feel I could be nurtured there. So, I left Detroit not for physical safety, but creative safety. If I wanted to grow as a writer, I felt like I needed to be surrounded by other writers who would be able to help me to become better with that.

But it is an interesting question to me, because I am actually now working on my follow up memoir. So, in 2005 I was writing for the Disney Channel, you know, starting to get my breaks in Hollywood as an Asian American writer, but then my parents were in a car accident back home in Detroit and my dad passed away. My mother was severely injured. Then my older brother, Chris, who’s a doctor, immediately whisked her off to northern California to help her recuperate. Then at the end of that first week all my other siblings decided to leave as well, they came to California to take care of my mom. So, there I was, back in Detroit, forced to ask myself whether I should go to Hollywood to help take care of my mom, or to stay in Detroit and take over the family business?

So, there is a lot embedded in your question that I am actively thinking about now. You know, like why did I leave in the first place? Why am I back now? How am I a different person? And so, I am thinking I’ll start with a new opening line, because the opening line of this book is “Welcome to Chung’s, is this for here or to go?” But now I am working with a new opening line, one that my dad would say when he knew someone was coming to dine in, which was “anywhere you like”. So, the new theme of this second memoir is “anywhere you like” . It’s like choosing a place to sit—that’s the fundamental question that I want to guide the second book. That balance between what do I like, what do I need, what makes me happy, all while grieving the loss of a dad and even the loss of a city. Because I’ve been thinking about this idea of recovery, because my mom was recovering…but the city wasn’t. So, these things are circulating in my head right now. Because the question inevitably impacts that second question about what it’s like to return.

Derek: I think that’s interesting because I am currently working on a project about recovery. The recovery of memory, of the self, of a sense of identity from being a place that you don’t totally identify with. It’s about trying to become comfortable with myself and how it feels to go back. And I think that’s something I am still working on, much like yourself, having a revelation about the self. So, one of the other questions I had for you was what you had to leave on the cutting room floor while writing this first memoir…

Curtis: Well, it’s almost about how much you want to reveal, right? It’s about how comfortable and about how much safety you feel, right? For me, obviously, the issue of being gay is like going back is like being back in the closet. But in terms of your politics, I would imagine that if you went off and started adopting these progressive positions—how much are you willing to share with your family back home? If you’re watching TV and they say something that’s problematic to you, do you speak up or do you let it slide?

Derek: Well, I used to speak up, I would say something to correct a misogynistic, sexist, or something political, but, like my Dad, he would take it as an insult to his intelligence. So, after a few physical altercations I think I quieted down. I quickly realized that, just as we were talking about earlier, some people you can’t reach—or not in that way.

Curtis: But then, the question I think we need to ask is what is the source of that anger? Where does this idea of disenfranchisement come from? I mean, we all have that ability to have that good side or that bad side. That’s why I don’t blame people like your dad. You know, he’s clearly listening to his friends or whatever media he’s talking about. That’s why, I think, it’s important for our leaders to encourage the good side in all of us, you know? To challenge those ideologies that maybe your dad has because he’s taking in that kind of media…

Derek: Well, you know, I think that’s part of it. I think also there’s the running joke when I come home “Ah, there’s the citified son! The liberal son!” I think one of the neighbors called me the enemy.

Curtis: And it’s sad to think that it doesn’t even pique their imaginations, you know? Because they know you, they grew up with you, and they still hopefully think of you as one of their own. But it doesn’t pique their curiosity that, “if I just read a couple of books I might think differently.” And then there’s the larger question that they don’t ask themselves, that if they meet people who are different from them that will change them, you know?

Derek: And I think that’s what I find interesting about you writing a second memoir…one that looks toward the questions that are left unanswered, or the impulse behind wanting those kinds of answers. But what’s fascinating is that by looking into these kinds of questions one has to turn towards the self and ask: am I the hero of the story? Or am I merely a person who also has faults? Do I, like those who seem to lack empathy, exist to simply try my best, doing what is right based on the knowledge that I have at my disposal.

Curtis: Well, I’ve not read a ton of memoirs, but I think there are definitely some that go to one of two extremes. On one end you have the speaker who operates as sort of this detached angel who is witnessing this crazy world. Then, on the opposite end, there are others that are sort of these misery memoirs that wrestle with a personal tragedy. But, for me, I want to strike a balance between those two because I think that sometimes we can be the hero of the story, but sometimes we can, frankly, be dicks due to our limitations and the way we might see a situation at that particular time.

Derek: But with that I think, in your book, you extend yourself a lot of grace, which is sometimes hard.

Curtis: Well, that’s easy because I’m old! Like, if I was that same kid…I would hate that person! I’m 56 years old, like, if I haven’t grown and become a better person then that’s the problem. Not that I don’t want to talk about it.

No, but there’s one thing I want to tell you. There’s one person in the book who I had to change her name because she was upset by the way I represented her. She was so pissed off at me when she read the galley because she thought I presented her in a bad way, as some cheap person. But the fact that she couldn’t get over her own personal growth, or laugh at her younger self, I mean… she doesn’t dispute that these things happened at all, but she just didn’t want them out there in the open air. But if you can’t laugh at yourself or take a bit of distance, I don’t think you’re ready to write a memoir, or write at all. In some ways you have to be open and willing to engage with people, with an audience.

Derek: I don’t want to guess at which character this is, but I assume that it’s one of the friends you have later in the book. If that’s true, I always found many of those characters likeable!

Curtis: Yeah! That’s what’s so crazy is that everyone who has read the book loves her! People will be like, that’s great that she stuck by you and you all remained such good friends! Readers all seem to agree that she was such a likeable character and a good person. But that’s what I mean: how you portray people, how they see themselves, is all tied into the writing of a memoir. At least for me.

There’s another story I’ll share with you. I was in Austin, Texas doing some pre-readings to sort of develop some hype before the book launched, and I call an Uber and I’m waiting outside the hotel and I see an older Chinese woman standing on the corner. She sees my ‘Detroit Versus Everybody’ sweatshirt and was like, “Oh, you’re from Detroit? I’m from Detroit, too!” And it turned out that her mom was best friends with my grandmother. And she started telling all these stories about my grandma being one of the best people she knew, “Oh, she always had candy in her pockets!” and I laughed and was like “That’s not the grandmother I knew.” But she tried to convince me that my grandmother was this great person, and I wasn’t trying to fight her because I didn’t want my grandmother going through life being unloved. But that love just wasn’t going to come from me because I had a different relationship with her.

Then the car came and I got in and went to lunch. But later I thought: that was my grandmother sending an emissary from the grave like, “How dare you say these things about me in your book!” But that just goes to show you that perspective is important when you’re writing, right? When you’re doing the writing, yes, you have a clear vision of who these people are. But keep in mind that other people may not, and if you open yourself up to those kinds of possibilities while you’re writing it may lead to a more complex understanding of the world. I couldn’t do that at the time because we had already gotten the book to the galley stage, but I would like to think I’d been doing that. So, I would say if there’s any one character that comes across as a little one dimensional it would be my grandmother. But even then, I think I still tried to find some compassion at the end, or an understanding of my relationship with her.

Derek: It felt like there was! Especially in the moment where your grandmother has fallen ill and your parents are sort of insisting on you not pursuing your summer plans to go to San Francisco. You turn to your mother, who you thought would support you given that your grandmother had always been mean to her in your eyes, and even she tells you to stay—that it’s your grandmother. I think, too, there’s even a moment where you help feed her?

Curtis: Yeah, I did help a little bit. I think, looking back, it was probably more out of some form of obligation and less out of an emotional attachment to her. But maybe there was…maybe it was just buried, because, you know, as kids you don’t always have full clarity of these kinds of situations. You still love your family, even if they are dicks to you on some gross, base level. But I think it was just a growth in the understanding of the relationship, because you don’t have to get to the point of total acceptance of these people. But what you do have to do is get to a point of understanding the situation, and the acceptance of that situation.

Derek: I like that. To get to the idea of acceptance of the situation at hand and not feeling like you have to change it. It’s like you said: sometimes these kinds of people won’t ever change.

Curtis: Yeah, or they’re not ready to change. Or they will never be able to change. I mean, the Chinese have this saying where you only change right before you’re going to die. And I remember always complaining, “Why can’t she just be a different person!” and, well, she did become a different person right before she died.

Derek: And speaking of endings, I think we are running out of time. So, we have time for one more question, if that’s okay?

Curtis: Sure, that sounds great!

Derek: So, towards the end of the book, you finally reveal to a friend that you are gay. And so, it’s this climactic moment where you can finally be free to be your true self! Then, when you all go to the strip club to celebrate and you find yourself being admired, it’s this moment where I found myself cheering you on and excited for you. But then you sort of pull back and we don’t get to see you, for instance, fall truly in love. And I think there’s something powerful in withholding something private within a memoir…,

Curtis: Well, and thank you for that, but the thing is that never happened. So, it wasn’t much me making an active choice not to include something. Instead, it was just me trying to accurately depict that moment.

Here, I’ll read a quick excerpt from a recent book review and see what you think about it, sort of regarding your question: “The universality of Chin’s story is one of its best qualities, while also being one of its most limiting. Chin’s prose is simple and straightforward, yet interesting. Making it both accessible and fun to read. He explains his life lessons in a way that is familiar and comforting. While these qualities make reading Everything I Learned…enjoyable, they soften some of Chin’s experiences and lessons. Because of this, some deeply transformational experiences he recounts fail to pack the emotional punch they should have. At the same time, though, much is gained through Chin’s writing style and his relatability often reads as intentional.”

So, it was interesting to me because she noticed what I wanted. In a memoir, is it necessary to push to that level? Why do you need to see those deeper moments? How much more insight do you need or want in my story? How much is enough? And the reality is that I might not even know. I’ve just always navigated life by moving on.

And so, I share that because I think that’s what I am now thinking about in terms of how to shape the next book. What do you think of that?

Derek: Well, I don’t see that as a weakness. I see it, in the book, as a huge strength. And perhaps that might be due to the fact I also operate in a similar way…I don’t linger on the past, but simply move on.that lack of total depth, or the depth that particular reviewer wanted, doesn’t feel real to me. What you offer in the book, though, does feel real, and that resonates.

Curtis: Well, and maybe it might be my safety? To pull back? And I think that’s okay! In the end, I think we are all human puzzles. There’s not a definitive answer, but instead an answer for now.

Like, how much do you have to dig into the truth? Because you have to admit, eventually, that particular truth is temporal. And maybe that’s a very Buddhist way of thinking about it. But, with that in mind, why put energy into that act? Isn’t it more important for an audience to feel connected to the story? And that particular review even says that—that she felt connected; however, she then wants more.

Like, the deeper question is: how much of a truthful narrator of your own life can you be? Right? We aren’t truthful narrators. We are limited. So, it would be easy to turn something into a sort of trauma-porn narrative because I’d know what it would do for a reader, but that would just be me selecting those items for the reader, right? Because I would then be doing it to elicit an emotion or a satisfaction that feels suspect.

Derek: And I think that’s what makes this particular memoir successful. Because you resist that urge, and you do portray an honest, or as honest as you can muster, recounting of your own story.

Curtis: Well, thank you so much.

Derek: Curtis, thank you. As I said, the book is excellent, and I cannot thank you enough for talking with me today. I very much look forward to the next book!

Derek Ellis was raised in the small, rural town of Owenton, Kentucky. He holds a B.A. in English Literature from Western Kentucky University and an M.F.A in Poetry from the University of Maryland, where he taught courses in creative and academic writing. He is currently pursuing a Ph.D. in English with a creative dissertation at SUNY Binghamton. His work is forthcoming or has appeared in The Academy of American Poets, Action Spectacle, BODY, Five Points, Leavings, Prairie Schooner, The Shore, and Waxwing.