GRIEF: A Walking Meditation

by Jacqui Higgins-Dailey

Inhale

A murmuration of starlings folds in on itself before blooming across the sky. Its formation appears erratic, like the staccato breath of a dog in a dream state. I imagine it as an intrinsic knowing; an inherited dance, finding rhythm like a sweetly choreographed impulse. Grief, too, is a wild thing. It takes no solid form or shape. When I think of the pulse and rhythm of grief, this murmuration comes to mind. I wonder why the breath of grief fills my lungs intermittently and without a clear pattern.

One afternoon, I hear comedian Mae Martin inquire if they are “full of birds” in their standup routine and I feel surprise relief. Someone else feels it too, the erratic pulsing. I only realized it’s grief after a panic attack at work. It was my evening shift shortly after COVID restrictions were lifted on campus and people were coming into the library again. I spent half my shift alone in my office working. My dog recently died. Four years earlier my mother-in-law and father-in-law died. Three years earlier my husband’s grandmother died. Two years earlier his aunt died. He has very few people left in his extended family and we rarely see them, if at all. My family is our family.

The panic attack hits as I stand up from using the toilet. I feel dizzy and disassociated. I don’t feel like myself but I also feel firmly inside a failing body. I grip the tile walls and take a breath, another. I wash my hands and find a mantra. This is an illusion, I say. But then I wonder, is it? Will I faint here in the bathroom inside an empty library? I don’t. I take a Xanax and walk around. I tell a coworker, the only other one in the library with me, that I think I am having a panic attack, just to hear myself speak. Oh, she says. My breath catches and snags. I go back to my office to do jumping jacks and convince myself I can breathe. The birds in my chest alight on a branch and I walk to my car and drive home.

I once told a close friend that I’d never pursue in-vitro fertilization (IVF) or any infertility treatments. If I couldn’t get pregnant naturally, then I would just accept it, move on. But no one tells you what it’s like to have a body that doesn’t work. No one explains to you the internal turmoil that results in realizing the one thing that everyone expects – the one thing that our culture tells us we are good for – is not an option. Who are women if not mothers? It’s a liminal space where I exist as a woman but not one with a child. I am expected and even encouraged to grieve the lack but not to be joyful in it.

The situations that trigger panic attacks are a mystery continuously unfurling before me. I’m learning to feel my way into them. When my anxiety feels activated, I pause and get curious. One early spring morning, I was packing to drive to Los Angeles for my dear friend Becky’s baby shower when I felt a swirl of nausea. I felt myself sway and sat down on my bed, my foot tapping as the tightly tucked bedspread wrinkled underneath me. The pillow caught my head and I checked my pulse on my smartwatch – 104 beats per minute.

I texted Becky, “Maybe I should fly.”

I looked out the bedroom window, framed by a slowly wilting fig and a bright, heart-shaped monstera plant. A hummingbird alighted on a stem outside, bowing to accommodate its weight, its magenta head illuminated in a lick of sunlight. I imagined the flutter of its wings matching the beat of my pulse.

I texted again, “Or maybe I can get Ken to drive with me. I don’t think I want to drive by myself. But also I don’t want to stress you out.”

I’ve driven myself from Phoenix to Los Angeles more times than I can count. Why suddenly did I need my husband to drive me?

The bird lifted off the stem and hovered in the air, gliding from one bloom to the next, taking what it needed before launching its small body straight up and cascading through the air, determined. I wished I was as sure about my next move as that bird.

Becky texts back, “k let me think on it! I’m not stressed!”

Then the realization drifts like a cloud into my awareness- I can’t go. Everything blurs.

Twenty-four hours later I hear back from Becky.

“Ok maybe this did stress me out,” she texts. Then she calls me.

“I guess celebrating pregnancy is a trigger for me,” I said. “I didn’t know, but it is. I can be around babies. I can hold and cuddle a baby. But celebrating the success surrounding pregnancy. I don’t know,” I trail off. It was the one thing I asked my body to do, over and over again, and it refused me.

She understands. She loves me. But after we hang up, exhaustion overtakes me and I fall asleep at six o’clock that evening. My muscles ache. The weight of anxiety spreads itself over me, bruising me from the inside out. My arms feel like they’ve been keeping to the beat of the hummingbird’s, a futile attempt at flight. As I drift off to sleep, I know I need to work through this. I know it will continue to hold power over me if I don’t.

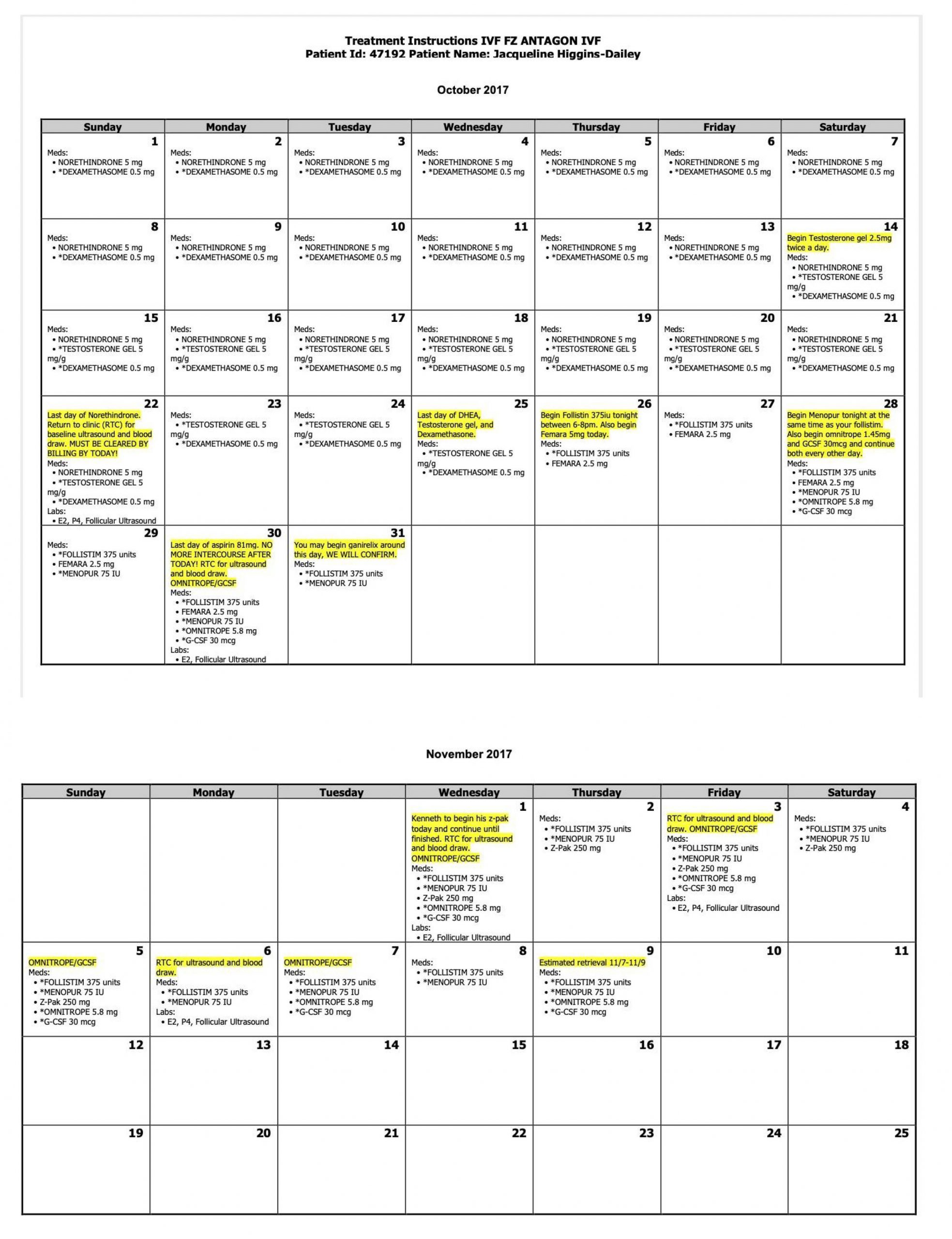

Retain

Before everyone in my husband’s family died, my hope of becoming a mother was taking its last, struggling breath. This breath stretched out until his grandmother’s death. It sputtered and ceased by Spring of 2020. That year I went on a pilgrimage in my city to walk myself into a decision. The question: do I continue IVF treatment? Over the past decade I endured two pelvic surgeries due to stage IV endometriosis and two failed IVF attempts. It was a period where I lost my body. I gave it up willingly. I injected myself with various gonadotropin-releasing hormones, human growth hormone, testosterone, and who knows what else. I submitted to transvaginal ultrasounds on a weekly basis, watching tiny, budding egg follicles bloom across the grainy landscape of my ovaries. None of this felt like a violation. I was being cared for and tended to. The nurses and doctors were charting my reproductive organs and drawing up a map for a destination that didn’t exist. I felt important, though. I felt like I had a purpose.

Those early morning ultrasounds, the meetings and plans, the mapping were all so carefully constructed. A trail etched into my psyche to guide me toward adulthood, womanhood. I’m a bit of a hypochondriac so these doctor visits also filled a need for me to be monitored and observed. If I had constant contact with healthcare professionals, I could rest assured that whatever might be wrong with me would quickly be discovered and remedied. It never occurred to me there was no remedy.

During treatment cycles, I would drive 25 minutes to my reproductive endocrinologist’s (read: fertility doctor) office nearly every other day in the early morning hours before work. The desert freeways I took to get to my appointments were empty of the morning commuters at that hour, my only companions were the tall, imposing saguaro cacti that dot the edges of the road, arms outstretched like goal posts. I’d say a little prayer to them to help me win this time. “Please just let this be the time I drive home with the news I want,” I whispered. But the saguaros knew better than me. They stood silent, patient.

I arrive at the fertility clinic just as its opening, walking down the sterile white hallways of the office complex and open the door to the lobby of the clinic where the sterility yields to blooms of flowers, positive affirmation wall art, a gently trickling water fountain, and a cheerful woman at the front desk. The best way I can describe the atmosphere is the way air freshener spray simply masks the foul odor of a bathroom.

When I’m called to the back, the nurse, a genuinely warm presence, greets me and my favorite part of the process begins- the care.

She puts her hand on my lap and asks, “How are you feeling?” as she guides me to lay back, feet in the stirrups. The whoosh and whir of the ultrasound machine kicks on as she probes around the tender swell of my ovaries, uterus, cervix.

“Full,” I answer as I sip a sharp inhale, the egg follicles dotting each ovary carrying a dull ache – both of wanting and pain when grazed. Each one stood for possibility.

“Well, you’re definitely full. Looks like we have about 4 mature follicles. I want you to take your trigger shot tonight and have intercourse and we will see you back here in a couple days for your IUI.”

IUI is intrauterine insemination – where they take your partner’s or donor sperm and inseminate you after medicated ovarian stimulation.

“Okay,” I say as I sit up, sweat beading on my brow and my eyes brimming for reasons I know and many I don’t. “Can I ask you a question?”

“Of course,” the nurse grabs a swivel stool and wheels it next to me, her eyes on mine and it’s as if the tears needed that eye contact and the levy behind them breaks. She gives me a sad smile. “Hang in there,” she says. “We can do this as many times as it takes.”

I nod. “How many people does this work for? Before they have to graduate to IVF?” I ask.

The pause she takes before replying is the only answer I need- not many.

_________

But that wasn’t the problem. Maybe I could have gotten pregnant if I had endless funds to funnel into IVF procedures.

One Sunday morning, not long before I would decide to stop infertility treatments, I was reading on my laptop, perched on a kitchen stool while Ken was frying eggs over the stove, spatula in hand; four slices of toast just pushed down into bright silver toaster we got for our wedding nearly ten years earlier.

“Jesus,” I said biting my lip, hunched over the keyboard, scrolling.

“What?” Ken asked.

“According to the Journal of the American Medical Association , women can increase their chances of having a live birth through up to nine IVF cycles,” I quoted from the article verbatim.

“Nine?” Ken said with a roll of his eyes as he gently picked up the egg, yellow yoke wobbling, and flipped it.

“You broke the yoke,” I said.

“Thanks. I see that,” he turns back toward his breakfast dance. The toast pops up. “I just don’t understand who is putting themselves through nine cycles of IVF. It’s expensive, but worse, it’s a constant science experiment with your body. It takes the magic out of it.”

“Yeah, I mean, I get it, but it also shows that if you just keep trying, it’ll probably happen. People who give birth have an average 30% chance after one cycle of IVF but that chance goes up to 77% after nine cycles.”

“Who are these people, though? Do they have endometriosis? Do they have a known issue? Or are they just going straight to IVF after a few failed attempts?”

It’s a fair question. Many people who undergo IVF treatment have “unexplained infertility.” This means they have no known reason or impediment to getting pregnant, they just aren’t.

“I don’t know,” I admit. “The article doesn’t go into the details.”

Ken flips the eggs back over and the yoke is cooked. “Well, it’s omelet day instead of runny eggs and toast day,” he said. I smile and he hands me the plate but I’m still finishing the article. A small part of me wants to know if I just did this at least nine times, would it work? Is there still hope?

But after going through just two cycles, I cannot imagine the emotional and physical exhaustion resulting from nine consecutive cycles of IVF.

As Ken sits next to me in his matching kitchen stool and tucks into his eggs, quietly scrolling his phone, I come to a point in the article where one researcher, when referring to women who failed to have a baby through IVF, is quoted in the LA Times saying that he “had a hunch that at least some of these women were giving up too easily.”

Giving up. Is that what I was doing? If only I didn’t give up, my dreams could be realized. Never mind that each round costs an average of $15k-$20k.

Ken looks up at me and smiles, “We’re already a family, Jac. No matter what happens.”

I give a small, half-smile back and take a bite of my eggs. “Thanks, Kenny. I know.”

______

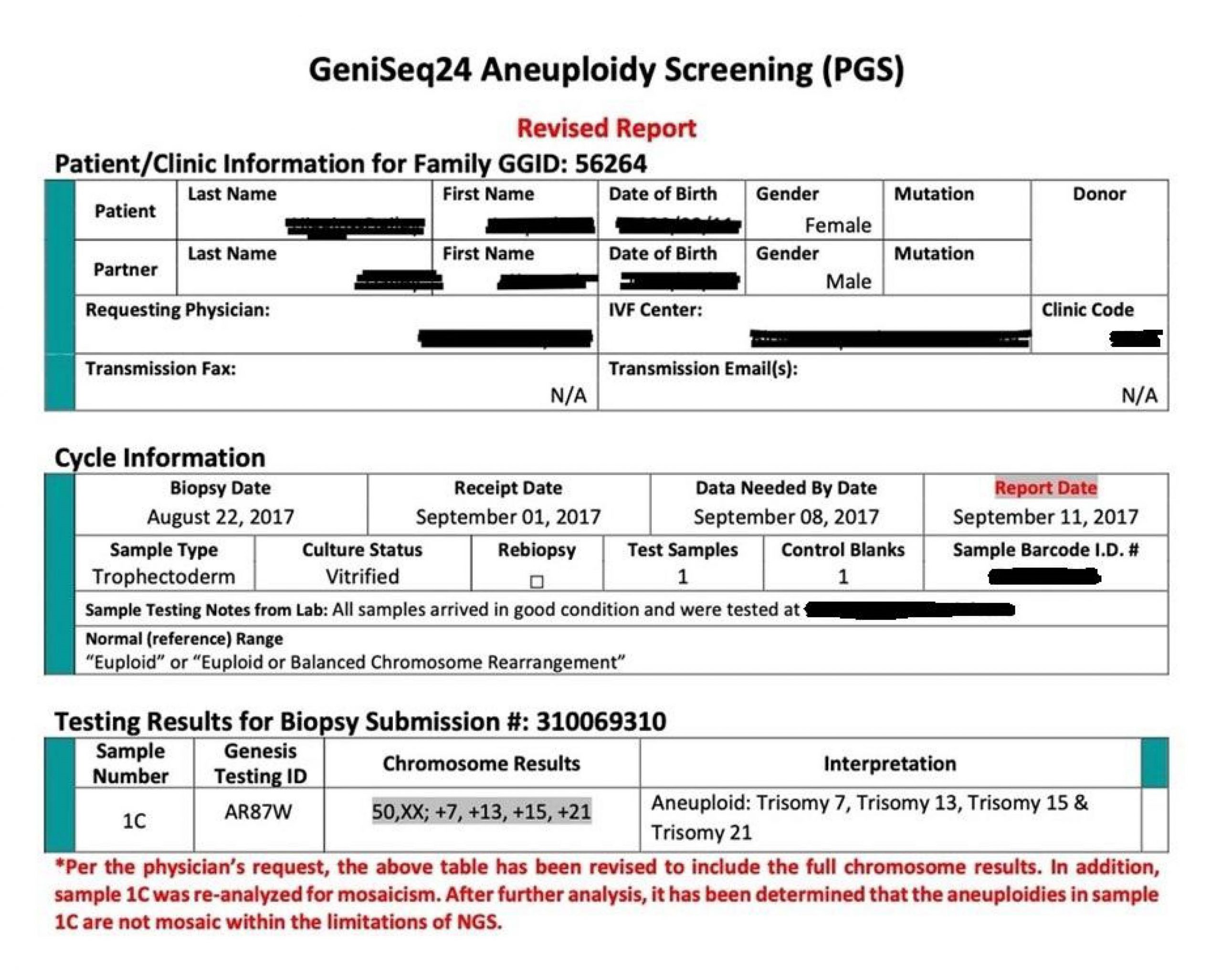

As a result of my second round of IVF, I have one female embryo. Genetic testing revealed it was high risk; a mosaic embryo. This means that it may have a serious and life-altering, if not life-threatening genetic disease, or maybe it doesn’t. A gamble my tired body seemed primed for but my mind was stuttering over.

In the winter of 2020, I woke up every weekday before dawn and walked the hiking trails of Phoenix Mountain Park. I thought I would find my answer. And I did. I planned to write about my experience, weaving my narrative of grief, loss and indecision with the stories of others who found solace in pilgrimage. But I didn’t.

The answer I uncovered was the simplest one. I decided not to continue pursuing pregnancy. I decided not to do another round of IVF; not to transfer my high-risk, mosaic embryo; not to continue to chart my organs and find a way to motherhood. I decided not to pursue adoption. I decided that the reason for my spiral into reproductive technology was to fix something that an external force was telling me needed fixing. My pursuit of pregnancy was an artificial attempt to blend in; find an identity. I decided, with my husband, that we were already the family we needed. I was tired and it was time to rest. I decided not to become a mother, ever.

For a brief time, we considered adoption. After years of failed treatments, adoption seemed like the natural next step.

We sat at our dining room table with an adoption agent on a summer morning as the cicadas began their electric hum. Forms and bright informational pamphlets were spread out in front of us like neon foliage. I wanted to rake it all up and toss everything in the bin. After years of charting my cycles, reproductive organs, and hormone levels, charting my personal life and finances seemed like too much.

“Adoption is not a cure for infertility,” the agent said. “This process is tough and just as emotionally challenging. The main difference is you will definitely end up with a baby in the end.”

I knew her words were meant as a cautious form of encouragement, but I swallowed them whole and they sat in my gut like an undigested meal. I shifted in my seat; crossed my legs and uncrossed them.

“Yes, of course,” I said, biting the inside of my cheek. “I’m so excited.”

About a month later, we were nearing the end of our required classes. We’d gathered with other hopeful couples each weekend to learn about everything we needed to equip us for this alternate route into parenthood. The classes were the first step and a required part of the process. Once we’re finished, we would create a book with pictures, bios, hopes and dreams, for the birth moms to go through and help them select the family they want to adopt their infant.

On the last day of classes, the adoption agency conducted a panel of adoptive parents and their young children alongside a panel of birth mothers. Babies were gurgling in their adoptive moms’ arms, toddlers were running around with their toys, and the hopefuls in the audience were cooing, their eyes welling up with every story and anecdote.

The agency requires open adoption, which initially, I thought made the most sense. I still think open adoption is the only way that seems ethical and fair to the women who choose not to parent their infants. But sitting there in the audience of that panel, I wasn’t sure of anything anymore.

The room was like any other corporate training room. The carpet a generic speckled gray and blue, the hard plastic chairs offering no cushion or comfort. The walls were covered in peeling, dated posters with images of babies in the arms of smiling adults with slogans like, “It’s in the love, not the blood,” and “Parenthood requires love, not DNA.”

Ken and I sat next to each other listening to the parents – adoptive and birth – and I noticed his eyes welling up from time to time. He’d reach to hold my hand, look at me with a question in his eyes – always, “are you okay?” I nodded. Yes, I was fine.

But after about 30 minutes of both warm and heart-wrenching stories of teenage pregnancies, the yearning mixed with relief in the birth mother’s eyes followed by tearful confessions by adoptive mothers and fathers of how desperate they were to have a baby, any baby, I began to squirm in my seat. A wave of exhaustion rolled over me and my eyes felt heavy. It was happening again. I bit my lip to stay awake. I started tapping my foot, knee bobbing up and down. Ken placed a hand on it to still me, eyeing me with concern.

I shrugged and tore a piece of paper from the notebook in front of me and wrote, “I don’t think I can do this,” and slid it over to him. He eyed it and nodded. He knew.

Very few people talk about the selfishness inherent in seeking to become a parent. But it was in stark display that day. When you choose to adopt, everyone says, over and over, how desperate they are to have a baby. How they cried every night for years to just acquire one baby, then two, maybe three. The anguish in the birth mothers’ voices, the desperation in the adoptive parents’ pleas. And how the success story looks like a strain from the perspective of the birth mother, who gave her child, but it looks like triumph in the eyes of the adoptive parents who received it. I couldn’t handle it anymore, this commodification of children. It was breaking me in a new way. Infertility broke part of me already, I couldn’t let adoption finish the job.

I don’t know what it’s like to become a mother, but I also don’t know what it’s like to want to be a mother that badly, maybe at all.

I stood up and hurried to the back exit, finding my way to the bathroom. I knew, then, that we wouldn’t move forward with the adoption process. I leaned against the door of the locked stall, let out a breath, closed my eyes, and cried.

______________

I finished my hikes right as the Sonoran Desert began to bake everything in its grasp. I imagined I would use my summer off to research women walking, men walking, the history of walking. But every time I searched for my voice it caught in my throat. My words didn’t come. My research was stilted. Writing without children was supposed to be the ideal. I had my freedom, so where was my creative spark? I read Rebecca Solnit’s book on wandering and her book on walking. I read Thoreau and Robert Frost. I found my answers. I was done yearning to become a mother but my grief is alive and breathing. It still consumes me and my writing. I don’t know how to categorize my grief – the loss of something I never wanted.

My desire to have a baby was a sort of cognitive dissonance. When I see babies, rather than want to care for them, I envy them. I get a warm, safe feeling thinking about curling up in someone’s arms; being gently tended to; tucked into a crib, lulled to sleep. When I think of the warm family life I fear I will miss out on, I often see myself as the child, rather than the mother. I see myself curling up in between two faceless parents, watching a movie, popcorn in a bowl. I want something that I don’t remember having as a child.

I spend most of my summers in New England and about two weeks with my friends Melissa and Bira in Vermont. They have one daughter, Calae, now seven years old. Interacting with my close friends who have children both buoys me in my resolve to not have them and stirs me in my grief over that loss.

When I visit, I give Calae the space I always craved from adults when I was a child. During the pandemic, two years passed since I had last seen Calae- from ages four to six- an eternity for a child. When I first saw her, she was sitting on her living room floor playing with a scattering of toys and dolls.

“Calae, Jacqui’s here!” Melissa announced as we entered the sliding glass doors, my suitcase trailing behind me. “She’s been so excited all week,” she whispers quietly to me as she puts the car keys down on the kitchen counter.

“Hi, Calae!” I said.

“Hi!” she said, a bright smile on her face, and turned back to her toys as I rolled my belongings to the guest room.

About an hour later Melissa and I were lounging at the kitchen table, sipping ginger tea that Bira prepared for us and catching up. Calae came over and asked if I wanted to see her toys. A slightly fuzzy family of palm-sized panda bears are lined up in a row, the mother panda has a pastel striped dress and the father, a pair of overalls. They appear to be having a picnic lunch with a rabbit family that has a set of triplets the size of my pinky-finger and all tucked into a miniature, baby-blue triple stroller.

“They’re Calico Critters,” she said proudly. “This family lives next door to each other and they’re having a picnic in the backyard. They forgot the carrots though, so the momma rabbit has to send the older brother back to the house to get them,” Calae said, the narrative unfolding as if these are just facts she’s relaying to me.

“Look,” she said and produced a carrot half the size of a toothpick. “I lost my Calico carrot so I made this one out of clay.” She hands it to me and it’s soft and cool to the touch.

“You made this?” I asked, honestly impressed.

“Yeah, I have a ton of clay so I can make Calico stuff – like carrots or even a knife or spoon. Whatever they need for their house or something.”

“This is so cool, Calae. I can tell you worked really hard making this look just right. It even has a tiny brown stem and a green stalk.”

“Uh-huh,” she said and then busily got on with the narrative, picking up the characters and having them talk to each other in various voices, mimicking babies crying for the triplets. She’s done showing me her toys for now so I sit on the floor and give her space, asking a question about Calicos every now and again until her next-door neighbor comes over to play “kittens” outside and she bounds off on all fours, meowing.

“You’re so good with kids, Jac,” Melissa says, watching from the table above. “So many people come on really strong and want to hug and play with her and it’s overwhelming for her. You just give her space and let her interact with you when she’s ready.”

“Really?” I muse. “I was worried you’d think I was being too aloof, but I just try to treat her the way I wish adults treated me.”

I’m a nervous adult and I was a nervous child. Whether that’s a result of my pre-determined personality or external influence is impossible to say. My grandmother had a phobic personality. My father is a hypochondriac, too. I was physically safe as a child but I never felt fully safe. I had parents, grandparents, aunts and uncles who cared deeply for me. But I was always holding my breath.

Later that summer, we were meandering through the woods, batting mosquitos and cocooned by beeches and maples, soft earth underfoot. Calae skipped ahead of us, voyaging off the trail, a stuffed kitten swaddled at her side in a repurposed swath of fabric made to be a baby wrap, her sing-song voice chatting contentedly to her small kitten.

Moments like these make me wonder if I made the right choice. It’s easy to imagine what motherhood might be like when I am with Calae. She reminds me of what I was like as a child, inquisitive, creative and curious; naive in the most precious way; anxious and shy. She’s delicate and strong-willed. I want to protect her and I feel myself wanting to protect the child I once was, too. But it’s a liminal feeling, this desire to both parent and be parented. I feel a disparate sort of loss, a feeling of nostalgia for something I never had.

In my search to find a word to connect me with this feeling of loss for something unknown or unrealized – I came across the Welsh word, hiraeth. The BBC describes this untranslatable word as combining “elements of homesickness, nostalgia and longing. Interlaced, however, is the subtle acknowledgment of an irretrievable loss – a unique blend of place, time and people that can never be recreated. This unreachable nature adds an element of grief, but somehow it is not entirely unwelcome.”

Hiraeth connotes a profound existential pain and has been used widely in Welsh poetry. A feeling more than a word, hiraeth is the closest I’ve come to finding a way to describe this amorphous grief of non-motherhood and nostalgia for my own infancy and dependance. Maybe this is more of a yearning for community and connection – something that seems even more elusive for child-free women. We don’t have play dates to bond within or school pick-up lines to chat. We don’t have postpartum support groups or nursing collectives. Where is our community? Our sisterhood?

Desperate to find answers to this question, I sought a therapist while I was undergoing infertility treatments. But invariably, the focus of the sessions – driven by the therapists – was my yearning for a child or discussions on how I felt about babies.

My first and last attempt at seeking therapy from someone who specializes in infertility started in a trendy office building with co-working spaces, sleek surfaces, and infinity pool water features. It felt like a knock-off version of what someone imagined the Google campus might look like and was unsurprisingly in Scottsdale, where everyone is trying so hard to look LA that they overshoot and end up looking like Miami.

I filled out paperwork waiting for my therapist and when she came out to greet me, she looked so out of place, it was glaring. She was middle-aged, kind-eyed, and had a matronly style about her that, in my mind, placed her browsing the aisles of Marshall’s. I imagined her picking out maxi skirts on sale and pairing them with flowy neutral blouses. She had a chocolate stain on her shoulder.

When I sat down, she gave me the look of sympathy that only people who have been through infertility understand, a head tilt, smile and a “keep-your-head-up,” sort of lift to her brow. Infertile women are grieving, but not really grieving anyone in particular, just the lack of someone.

“I see you’ve been going through quite a few years of fertility treatments,” she opens with. “I know how difficult that can be. I went through many myself.”

“How did it end?” I asked.

“How did what end? My treatments?”

“Yes,” I say, knowing what the answer will be. “Did you get pregnant?”

She looks a bit chastened, folds her hands in her lap. I look at the diplomas on her wall, the framed photo of a toddler, maybe three or four years old.

“I did,” she said. “It was a long road, though. And I only had the one,” she vaguely gestures to the photo I’ve already seen.

“I guess I’m trying to figure out why I wanted a baby so badly. Who I might be outside of that desire,” I change tracks. I don’t want to hear her success story. I’m here to talk about me.

“What made you want to become a mother? I know that yearning can be so visceral. How does that manifest for you?” she asked.

“I don’t think it has manifested. I think I just wanted my body to work, to do what it was supposed to do and when it couldn’t, I became fixated on getting pregnant but never really played it all the way out into having a baby.”

“What do you think it would feel like to play that out?” she asked.

“I don’t know. I don’t want to play it out. I want to think about what it might be like if it never plays out.”

“Do you think that has something to do with your anger right now? Maybe you’re channeling it toward the outcome you fear?”

“I don’t know. I don’t think so. I don’t think I fear not being a mother. Or maybe I do? I just think I want to imagine what life will be like if I belong only to myself.”

The therapist looks at me perplexed. And I understand, she didn’t anticipate me. She was used to talking to women still yearning to become mothers. It never occurred to her that some of us are not.

I never get what I need from people who are still trying to fix my flawed reproductive organs; trying to give me hope to keep going when all I wanted was permission to stop. I craved an honest conversation about how womanhood manifests without children. I wanted to talk about what that life would look like and how maybe my desire was misplaced longing. I wanted my therapist to talk about a fulfilling life that didn’t include motherhood.

Infertility “support” groups online are rarely supportive to women who decide to stop treatment without getting pregnant. Women berate other women who validate the choice of “giving up.” If you fail to have a baby, you’re a quitter. The slogan across most online forums is “never give up hope.” But what happens when that hope transforms? When you wake up one morning and realize hope manifests in as many ways as joy; hope for a life full of love, hope for strong relationships, hope for rest, hope for freedom. Our bodies are tired and when we tap into that deep intuition, we hear the cry for a new kind of hope. We come back to ourselves and realize we don’t need anything else.

Ruby Warrington, in her recent book Women Without Kids had a similar experience in reaching out for therapy and being met with a therapist who only wanted to explore why she doesn’t want to (and has never wanted to) have kids, as if it’s some kind of pathology. But she also makes note of both the conscious and unconscious suffering of women who are traversing the deviant path of non-motherhood. This unconscious suffering, she says, keeps us stuck in repeating patterns of the past while the conscious suffering of going against both “familial and societal expectations” is what might liberate us. “For many women without kids, this will mean living in defiance of the conditioning that says a woman is only as valuable as her reproductive capacity…” she laments.

I want to channel my nervous nature into a new hope; a transformation within myself. Understanding who I am as a woman within the confines of patriarchy is nearly impossible when the only acceptable definition of womanhood is how capable my uterus is. Without it, I am an extra; a disposable cast member in the patriarchal theater. After getting married, when faced with the ever-present question- when are you having a baby? – my worth was always on display. When I have a baby, I will have fulfilled my role. When that didn’t happen, I became a lesson. Freeze your eggs or you’ll end up like Jacqui. You don’t want to be like me. I am nothing.

Melissa Febos, in her book Body Work, talks about the stages of trauma recovery and how these stages interweave within the work of a memoirist. Writing a personal narrative forces people to confront trauma and work through it on the page. She says, in reference to the continuum of trauma healing, that it comprises “three approximate phases: the establishment of safety, constructing or completing the narrative of the trauma, and the return to social life.” I am still working on all three, simultaneously. I don’t believe it is a linear process – maybe I will always be working through these stages. Do I have internal psychological safety? I often berate myself and wonder why I can’t work through this loss without needing validation. Am I completing the narrative of the trauma with these words? I hope so. I have returned to social life – I talk about my trauma freely. If I am asked about my state of parenthood or non-parenthood, I tell the truth even when it makes people uncomfortable. The discomfort that results is not my problem. The question is the problem. I am making new discoveries about myself and my trauma daily, so I imagine I will always be working through it.

I always thought my anxiety was rooted in fearing the unknown, but it has become clear that knowing is more stymying than wondering. The truth is more terrifying than any fiction I create. Because I must face the truth.

I will not have children. The act of trying each month was like a puzzle. If I could fit the pieces together, at the end I may end up with something whole. A fetus; infant; toddler; child. But pieces were missing. The puzzle didn’t form anything cohesive. I am already whole. There was no puzzle at all.

Exhale

I still hike or walk nearly every morning. Strolling mountainous trails improves my mood. I feel happier, more hopeful. With hindsight, I realized it’s best I made my decision not to continue IVF during these morning hikes. I was contemplating the question through a lens of hopeful grief and joy, rather than one of melancholy. The hikes themselves were answers to my question. Each step a reply. The long, craved stretches of solitude would be nearly impossible to endeavor while caring for a young child.

I knew I was walking myself into freedom. And while freedom has the potential to be lonely, mystifying, confusing – it’s up to me to choose how freedom manifests. I often confuse loneliness with solitude, yet they are only differentiated by perception.

In her book, The Wisdom of Not Knowing, psychotherapist Estelle Frankel describes a Kabbalistic concept called ayin as “the realm of divine nothingness.” All thought and creative expression are born from within this “fertile void” of ayin and return to it in a continuous cycle of birth, death, and renewal. “By taking us to a place beyond thought and form, ayin makes room for new thoughts and creative impulses to emerge,” Frankel explains.

I found my answer to an intimate existential question by releasing it into this fertile void, walking in silence, and trusting (and sometimes not trusting) that an answer would manifest. There were days I would doubt everything and feel foolish for thinking that walking every morning would bring me answers to anything. But one day, in a moment of epiphany, it happened. I uncovered my answer. I listened to myself in a way I was unable to with the cacophonous noise of societal expectations that came through as advice from family, friends, doctors – but rarely from my own intuitive sense. The silence brought me back to myself.

Frankel notes that according to the mystic, Aryeh Yakov Lieb, each time we ask ourselves existential questions, we unlock new doors and new understanding. As we continue to grow and change, so do these new “levels of understanding” and we then seek the answers to new questions through deep listening “until our silence becomes what Leib calls ‘a pregnant silence’ – one that gives rise to a whole new level of understanding. We have entered the next level or world, where a brand-new paradigm informs our lives. And this progression goes on infinitely.”

The birthing and rebirthing of our own existence is a labor in itself. It’s painful, transformative, and opens us up to revelations of how to love ourselves better; to give ourselves renewed and constant grace. This is the threshold I hope I stand within today. It’s a liminal space. I’m doing my best not to fear the light shed, one step at a time, before me. I am walking gently, holding my own hand; reparenting myself.

I wake up before the sun, lace up my hiking boots and drive up the road to my neighborhood mountain trail. I don’t bring earbuds. I prefer to listen to the pre-dawn birdsong; the rolling call of the Gila woodpecker; the buzz and chip of an Anna’s hummingbird; the scree crunching underfoot. I listen closely to myself. I tune into my own rhythms- my pulse as it quickens and slows from each climb and descent. The cold desert air feels like an embrace, so I lean into it and let it carry me forward.

Jacqui Higgins-Dailey holds a bachelor’s in journalism from California State University, Chico and a master’s in library science from the University of North Texas. She’s an incoming student in the MFA program at the University of New Orleans and has a variety of fiction and nonfiction published in NPR, The Rumpus, the ALA’s Office for Intellectual Freedom, and The Journal of Intellectual Freedom and Privacy. She is residential faculty at Glendale Community College in Arizona.